Effects of AGW on Wildfires in the Western U.S.

|

| Relationship Between Temperature and Wildfire Frequency, Season Length and Spring Snowmelt |

This is part 2 of a two-part series on wildfires in the U.S. Here's part 1, where I look at the evidence for how wildfires have increased in the U.S.

By all accounts the relationship between wildfires and climate change is complex. In fact, it's probably fair to say there are to some extent two competing trends globally. Warmer temperatures from increased GHGs lead to more water vapor in the atmosphere which should increase rainfall in some areas of the world. But in more arid climates, like in the western U.S., warmer temperatures can increase aridity. Increased vapor pressure deficit (VPD) leads to decreases in soil moisture; plants dry out and become flammable more quickly, so wildfires can ignite and spread more quickly. This is not to say that AGW actually starts wildfires. Sources of ignition are still predominantly human behavior (as in carelessness with cigarettes and camp fires) and lightning strikes. Some studies show that perhaps 85% of ignitions are due to human behavior, and of course this will have a significant impact on acres burned each year. But we are not here looking at sources of ignition. We are considering evidence for the effects of climate change on acres burned - that is, to what extent AGW has an impact on making ignitions more likely and wildfires to spread more quickly.

It's fair to say that our forests in the American West are under attack from human activity. Most of this is unintentional; we're not trying to destroy our forests, and climate change is one aspect of a complex network of human impacts on our forests that are making wildfires more common and severe. This complex network includes 1) direct effects of GHG warming, 2) forest management, 3) invasive species, and 4) degraded ecosystems from AGW. Climate change is affecting wildfires in the American west both directly, by creating hotter and drier conditions, and indirectly, by making our non-climate-related bad behavior worse. Let's look at each of these in turn.

Direct Effects of GHG Warming

It's no secret that hotter, drier condition make wildfires more likely to start and become more severe. As temperatures rise, the atmosphere can hold more water vapor. In arid climates, vapor pressure deficit, which is the difference between how much moisture is actually in the atmosphere and the moisture that the atmosphere can have at saturation. As VPD increases, the atmosphere takes moisture from soils and plants, making an arid climate even more arid. Warming temperatures[1][2] also mean that temperatures are warm enough for wildfires to ignite more days out of the year, lengthening the fire season. And decreased snowfall in winter leads to less Spring snow melt to provide moisture to arid climates. One recent study found that:

The duration of the fire-weather season increased significantly across western US forests (+41%, 26 d for the all-metric mean) during 1979–2015, similar to prior results (10) (Fig. 4A and Table S2). Our analysis shows that ACC accounts for ∼54% of the increase in fire-weather season length in the all-metric mean (15–79% for individual metrics). An increase of 17.0 d per year of high fire potential was observed for 1979–2015 in the all-metric mean (11.7–28.4 d increase for individual metrics), over twice the rate of increase calculated from metrics that excluded the ACC signal (Fig. 4B and Table S2). This translates to an average of an additional 9 d (7.8–12.0 d) per year of high fire potential during 2000–2015 due to ACC.[3]

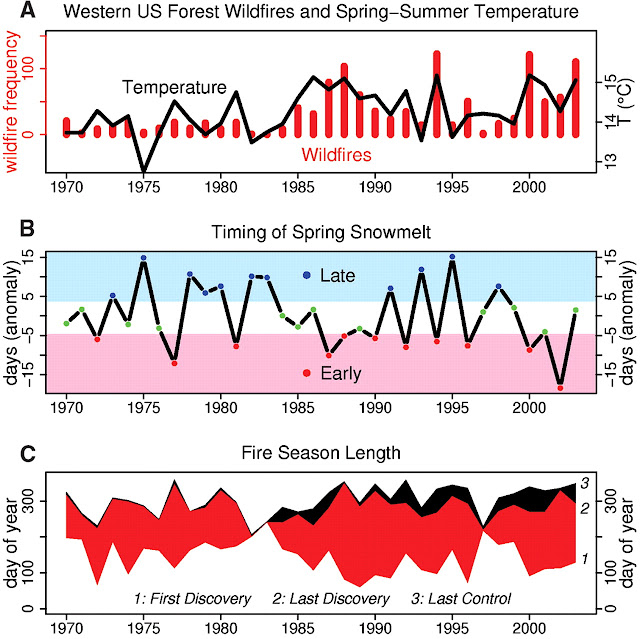

The paper concludes that AGW is responsible for "over half of the documented increases in fuel aridity since the 1970s and doubled the cumulative forest fire area since 1984." In fact, it seems in the western U.S. the mid-1980s was marked by a transition from a relatively low frequency of large wildfire activity to one with increasingly longer burning fires, and the drivers of this transition have to do with the effects of climate change, including warmer, drier springs with reduced winter snow, earlier snow melt and drier summers.

Robust statistical associations between wildfire and hydroclimate in western forests indicate that increased wildfire activity over recent decades reflects sub regional responses to changes in climate. Historical wildfire observations exhibit an abrupt transition in the mid-1980s from a regime of infrequent large wildfires of short (average of 1 week) duration to one with much more frequent and longer burning (5 weeks) fires. This transition was marked by a shift toward unusually warm springs, longer summer dry seasons, drier vegetation (which provoked more and longer burning large wildfires), and longer fire seasons. Reduced winter precipitation and an early spring snowmelt played a role in this shift. Increases in wildfire were particularly strong in mid-elevation forests.[4]

Overall, the evidence is clear that AGW is changing the American West to make the area more conducive to wildfires. Wildfires can ignite and spread more easily now because of the direct effects of climate change.

Forest Management and Fire Suppression

The devastating wildfire in 1910, often referred to as the "Big Burn," struck when the U.S. Forest Service was in its infancy, and compared to today, they knew very little about what causes wildfires to go out of control, as this one did, and they had little knowledge about how to fight these fires. In his book The Big Burn [5], Timothy Egan tells the gripping (and sometimes gruesome) story of how the fire started and devastated parts of Montana, Idaho, and Washington. Many firefighters dies in the effort, and the effects on the USFS were profound. Fire prevention and suppression became a top priority of the USFS for decades. Over the years, in many parts of the U.S. this led to a buildup of "fuel" on the forest floor - dead and decaying wood that can dry and allow wildfires to ignite and spread more quickly. In the 1960s, developments in forest ecology led to revisions of this policy, and the USFS changed their fire suppression policies and even began to practice prescribed burns. Today, you can sometimes also see piles of dead wood collected along the forest floor to limit the available fuel for wildfires. As a result, while fire management is certainly a factor, it's also a factor that is being corrected. One study estimating wild fire acres burned (WFAB) concludes thatDespite the possible influence of fire suppression, exclusion, and fuel treatment, WFAB is still substantially controlled by climate. The implications for planning and management are that future WFAB and adaptation to climate change will likely depend on ecosystem‐specific, seasonal variation in climate. In fuel‐limited ecosystems, fuel treatments can probably mitigate fire vulnerability and increase resilience more readily than in climate‐limited ecosystems, in which large severe fires under extreme weather conditions will continue to account for most area burned.[6]

But to whatever extent forest management continues to be a problem, it is also a problem that AGW makes worse. AGW increases the speed at which dead wood dries out and becomes suitable fuel for wildfires. This is particularly true in Northern California.

Changes in Northern California forests may involve both climate and land-use effects. In these forests, large percentage changes in moisture deficits were strongly associated with advances in the timing of spring, and this area also includes substantial forested area where fire exclusion, timber harvesting, and succession after mining activities have led to increased forest densities and fire risks.[4]

In other words, the this is not a climate change vs forest management argument, as if wildfires are worse either because of climate change or forest management. In reality, this is a problem in which forest management is a significant factor, but AGW is making it worse than it otherwise would have been.

Invasive Species

The effects of invasive species on our forests and grasslands (and other ecosystems) are widespread and profound. I live in Florida, where tropical exotic species are common place from escaped (or set free) pets. Brown Anoles, Cuban Treefrogs, iguanas, and parakeets are some of the most noticeable, but the problem is far more pervasive, and the effects are far reaching. In a few instances, invasives provide some benefits to some species. Invasive Apple Snails are allowing Snail Kites and Limpkins to become more common and expand their ranges northward in Florida. But for the most part, invasive species degrade habitats and diminish biodiversity. In some of my favorite local hiking destinations near my home, invasive Caesarweed has all but taken over some of our forests. You see trees and Caesarweed, and that's about it.

But in the American West, some of these invasive species are altering the fire landscape and contributing to the increase wildfire activity. One of the chief offenders here is cheatgrass and other annual grasses. As these flammable grasses dominate habitats, wildfires and start and spread more quickly. As climate warms, cold-intolerant invasive grasses may be able to out-compete their native counterparts, and as they die and dry more quickly, they make wildfires a larger problem they otherwise would be.

Results suggest widespread changes in 1) the length of the freeze-free season that may favor cold-intolerant annual grasses, 2) changes in the frequency of wet winters that may alter the potential for establishment of invasive annual grasses, and 3) an earlier onset of fire season and a lengthening of the window during which conditions are conducive to fire ignition and growth furthering the fire-invasive feedback loop.[7]

Invasive cheatgrass, in particular, makes wildfires more common, and as those sites burn, more area becomes conducive to becoming cheatgrass grasslands, and this becomes a "fire-invasive feedback loop."

Here, we have documented that cheatgrass-dominated areas, which currently cover ~40,000 km^2, sustain increased fire probability compared with native vegetation types. As sites burn, more and more of them are likely to become cheatgrass grasslands thus increasing their future probability of burning. If future climate scenarios hold true, the combination of warmer temperatures and high water availability could yield larger fire events that are carried between forested or shrubland areas by invasive grasses, thus perpetuating a novel grass-fire cycle across the western United States and ultimately reducing cover of woody species.[8]

Invasive species are having a tremendous impact on our ecosystems apart from climate change, but with climate change, the problem is becoming worse. And it appears to be self-perpetuating. Invasives are making wildfires worse, and climate change is favoring invasives. As wildfires increase, conditions become even more favorable to invasives, which in turn makes wildfires more likely.

A warming climate in the American West also has wide ranging impacts on native species, not just invasive species, and those impacts can degrade ecosystems in such a way that wildfires become more common. The most notable example of this is the increased destruction from Bark and Pine Beetles in the western U.S. These beetles are capable of eruptive population growth, and they can destroy entire landscapes, causing wide spread tree mortality. The last time I visited the Rocky Mountains, I saw large patches of dead trees caused by pine beetle infestations. These infestations leave acres of land with dead wood that quickly become fuel for wildfires. As these species proliferate in forests, wildfires become more common.[9][10]

But these beetles are not invasive. They are native species, and trees where they live have developed defenses against them. But as climate warms, the beetles are able to move to higher altitudes and higher elevations, where trees have not needed these defenses, so they aren't adapted to them.[10] Warming also allows these beetles to reproduce more quickly, which in turn allows them to do more damage during outbreaks.[11] So these beetles are able to cause more damage now than they could in the past, since more forested land is available for them to invade with fewer defenses against them. The increased tree mortality due to climate change then produces more fuel for wildfires in conditions also made hotter and drier because of climate change.

Conclusion

As climate change continues, its effects are likely to be increasingly felt in the American West. It's causing droughts[12] to become increasingly severe and common, and they are lasting longer.[9] This depletes groundwater reserves and makes wildfires more likely. It is certainly true that wildfire alone isn't directly responsible all of this. A fair and balanced treatment of the American West will acknowledge that AGW is responsible for some of this, and it's making other facets of the problem worse. It should also readily apparent that this is unquestionably a negative impact that human activity is having on our environment, and in turn we are causing harm to ourselves. AGW is responsible for roughly doubling the cumulative acres burned in the western U.S. since the mid-1980s, and this trend is not likely to change for the better until we address its causes. It requires efforts not just to limit our impact on climate but to control invasive species and continue to improve our forest management.References:

[1] Tang and Arnon, "Trends in surface air temperature and temperature extremes in the Great Basin during the 20th century from groundbased observations," Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 118 (2013): 3579–3589.

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jgrd.50360

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jgrd.50360

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/43dc/df32d6c0fa6a3f64e3afa5a19b8635dd5627.pdf

[3] Abatzoglou and Wiliams, "Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests" PNAS October 18, 2016 113 (42) 11770-11775

https://www.pnas.org/content/113/42/11770

https://www.pnas.org/content/113/42/11770

[4] Westerling, et al, "Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity" Science 313.5789 (Aug 2006): 940-943.

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/313/5789/940

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/313/5789/940

[5] Timothy Egan. The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America. Mariner Books; Reprint edition (September 7, 2010)

[6] Littell, J.S., D. McKenzie, D.L. Peterson, and A.L. Westerling, 2009: Climate and wildfire area burned in western U.S. ecoprovinces, 1916-2003. Ecological Applications, 19 (4), 1003-1021.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/07-1183.1

[7] Abatzoglou and Kolden, "Climate Change in Western US Deserts: Potential for Increased Wildfire and Invasive Annual Grasses" Rangeland Ecol Manage 64:471–478 | September 2011

http://www.pyrogeographer.com/uploads/1/6/4/8/16481944/abatzoglou_kolden_2011_rem.pdf

[8] Balch et al, "Introduced annual grass increases regional fire activity across the arid western USA (1980-2009)" Global Change Biology · March 2013

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gcb.12046

[8] Balch et al, "Introduced annual grass increases regional fire activity across the arid western USA (1980-2009)" Global Change Biology · March 2013

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gcb.12046

[10] Barbara Bentz. "Bark Beetles and Climate Change in the United States." https://www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/bark-beetles-and-climate-change-united-states

[11] Hanna Grover. "Study: Warming climate leads to more bark beetles killing trees than drought alone."

[12] Williams, A. P., R. Seager, J. T. Abatzoglou, B. I. Cook, J. E. Smerdon, and E. R. Cook, 2015: Contribution of anthropogenic warming to California drought during 2012–2014. Geophysical Research Letters, 42 (16), 6819–6828. doi:10.1002/2015GL064924.

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2015GL064924

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2015GL064924

Comments

Post a Comment