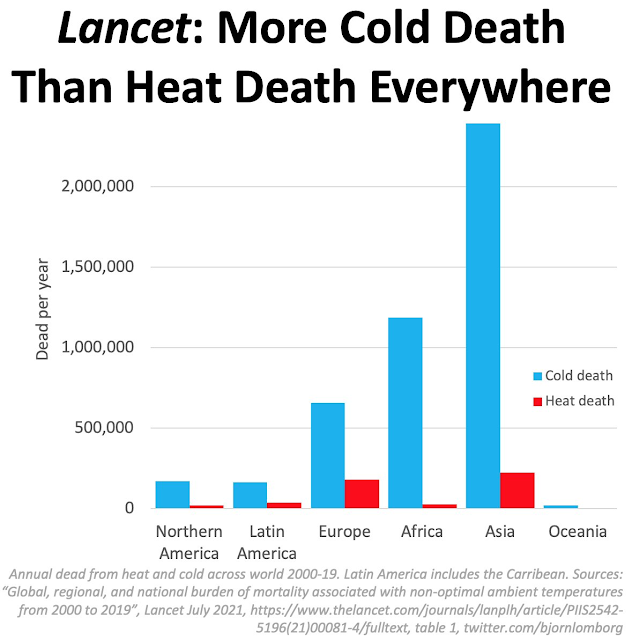

If you follow contrarian talking points on social media, you might get the impression that cold weather kills more people than hot weather, and so global warming will result in fewer deaths, and lives will be saved as the planet warms. You can see this in this graph from Bjorn Lomborg, based on a Lancet study[1] that quantifies "cold-related" and "heat-related" deaths.

This kind of thinking may seem superficially convincing, but with a little investigation, much of what is being said by Lomborg (and others) is incredibly misleading. It's based on a misunderstanding of what these types of studies say, as well as some flawed logic about how deaths will be affected by warming.

Cold vs Hot Related Deaths

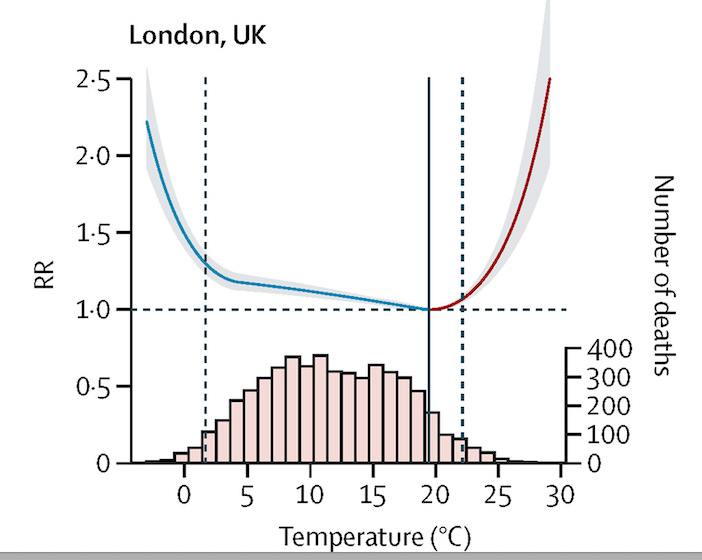

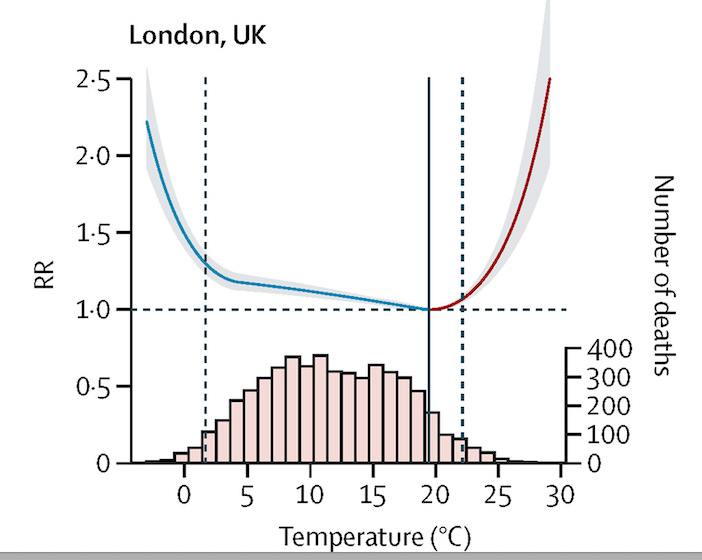

This Lancet paper is one of many[2][3] based on a concept of "minimum mortality temperature" (MMT), which is defined as the mean temperature at which non-accidental death rates in any particular location is the lowest. In most places the mortality rate is lowest at around 20 C, so these papers attribute all non-accidental mortality above MMT as "temperature-related" (not specifically temperature-caused). Excess mortality at temperatures below MMT are labeled "cold-related," and excess deaths at temperatures warmer than MMT are "heat-related." So, for example, if the MMT of a city is 20 C (or 68 F), and the mortality rate at MMT is 50 people/day, then deaths above 50 people/day at other temperatures contribute to the relative risk for that temperature, which can be calculated by taking the death rate at any given temperature divided by the death rate at MMT. So if at 18 C the mortality rate is 60 people/day, then the relative risk at 18 C is 60/50 = 1.2.

This metric means necessarily that all non-accidental deaths at temperatures exceeding the death rate at MMT are going to be put into the category of "cold-related" or "heat-related" even if the temperatures are mild. Since MMT in most locations is in the mild range (20 C is 68 F), many of the "cold-related" deaths occur in mild conditions (18 C is 64 F). And since people die every day regardless of the weather, and since most days in mid-latitudes are not extremely hot or cold, deaths tend to bunch up in relatively mild conditions - there are simply more days out of the year for people to die when temperatures are mild.

What this metric tells us is that more deaths occur at temperatures below MMT than at temperatures above MMT, even though most deaths occur at temperatures near MMT when temperatures are generally mild. This is a point that is frequently made in these kinds of studies. Here's a statement in a recent paper[4] published examining cold-related and heat-related mortality in 106 cities in the United States.

Although 86% of temperature-related deaths are due to cold-related mortality (4,819 heat-related deaths, 31,625 cold-related deaths), most of these “cold-related” deaths occur at temperatures only slightly below the MMT, which is typically around 22°C. For example, 26% of cold-related mortality is occurring within 5°C of the MMT, with an inter-city standard deviation of 11%. While the risk of temperature-related death at these pleasant temperatures is low, their frequent occurrence still contributes to a significant number of deaths, a point also highlighted by Gasparrini et al.

and again:

We estimate that there was an average of 36,444 temperature-related deaths per year during the period 1987–2000 in the cities in our data set. Consistent with previous work (Berko, 2014; Gasparrini et al., 2015a, 2017; Heutel et al., 2021), we find that 86% of these deaths were cold-related. Most of the cold-related deaths took place at moderate temperatures just below the MMT, typically around 20–22°C, so they are categorized as cold related even though many would consider the temperatures to be mild.

These studies confirm that that indeed significantly more people die in weather colder than MMT than above it, but they do not say much about temperature extremes or deaths that are determined to be caused by hot or cold temperatures.

However,

the NWS has performed an analysis that essentially counts deaths that are determined to be from hot or cold. NOAA quantified deaths determined to be caused by heat vs cold for 2022 and 10-year and 30-year averages. By this metric, deaths due to heat far outnumber deaths due to cold by a significant margin. Below I show a plot of NWS data for hot vs cold fatalities in the US since the 1980s (2024 numbers are preliminary).

.png)

These two statements may superficially seem to be at odds with each other, but in fact they are compatible. For instance, if at temperatures below MMT people are more likely to go out and enjoy the ideal weather by running or cycling, and if that leads to an increase in heart attacks from over-exertion, then those deaths would be counted as "cold-related." Even though the cause of death was due to exertion, the mild temperatures make it more likely for people to go outside and exercise, putting themselves at risk for heart attacks. Using a MMT metric, an increase in heart attacks at temperatures lower than MMT would count as "cold-related" deaths, but in NOAA's metric they would not. What this means is that while it's true that "cold-related" deaths far outnumber "heat-related" deaths by a MMT metric, it's also true that the deaths determined to be from heat significantly outnumber deaths determined to be from cold.

How Global Warming Affects Mortality Rates

So we've seen already that it's simplistic to say that cold kills more than hot without significant qualification. But there's also a logical error that is implicit in claims that global warming will cause a net decrease in mortality. That is, it's a non sequitur to claim from this that AGW will save lives. Even using a MMT metric, that conclusion simply doesn't follow. While it's true that warming should cause a decrease in cold-related deaths and an increase in heat-related deaths, that does not say much about how cold-related and heat related deaths will change with global warming. For example, if currently there are 1000 cold-related and 100 heat-related deaths, but at 1 C warming, cold-related deaths decrease to 950 and heat-related deaths increase to 200, then there will be a net increase in mortality even though cold-related deaths continue to far outnumber heat-related deaths.

Using the MMT metric, whether warming will increase or decrease relative risk of temperature-related deaths depends on the distribution of deaths relative to MMT. Andrew Dessler has an excellent article explaining this at

The Climate Brink. Graphs of relative risk tend to be U-shaped, showing declines in risk below a certain threshold and steep increases in risk above a certain threshold, as you can see in the above graph from London. The distribution of deaths is shaped similar to a bell curve. The graph above originates from Gasparrini's paper[2] but is used in Dessler's article as well. Most days in London are below MMT, and so currently most deaths are cold-related. As London warms this distribution will shift to the right (let's assume that the shape of the distribution doesn't change), and a higher fraction of deaths will occur at temperatures higher than MMT - cold-related deaths decrease and heat-related deaths increase. In London, a little warming will thus cause a net decrease in mortality, to a point. Because relative risk steeply increases above ~22 C, eventually London will experience a net increase in mortality due to warming, even tough cold-related deaths will still outnumber heat-related deaths.

This is more typical in the mid-latitudes, but many tropical areas are not so lucky. Given the distribution of mortality and relative risk in places like Bangkok, Thailand, where "the temperature distribution is centered on the MMT," warming will cause a near immediate increase in mortality.

Lee and Dessler's paper[4] examining temperature-related mortality in the US confirms that there will be a short-term benefit for US cities up to about 3 C of global warming.

We find that temperature-related deaths increase rapidly as the climate warms, but this is mainly due to an expanding and aging population. For global average warming below 3°C above pre-industrial levels, we find that climate change slightly reduces temperature-related mortality in the U.S. because the reduction of cold-related mortality exceeds the increase in heat-related deaths. Above 3°C warming, whether the increase in heat-related deaths exceeds the decrease in cold-related deaths depends on the level of adaptation.

However, they are careful to point out that these results in the US are not likely to be replicated in other areas of the world, especially in areas with less ability to adapt to a warming climate. They write,

we cannot comment on the future of heat-related mortality in the rest of the world. However, given the wealth of the U.S., our present levels of adaptation are higher than in many poorer countries and our ability to enhance our adaptation is also higher. Thus, it seems likely that heat-related mortality will be a more significant problem in the rest of the world as climate change progresses through the century.

Estimates of the global impact of global warming also expect a net increase in deaths with global warming - heat-related deaths will increase at rates higher than cold-related deaths.

|

| Bressler 2021 |

And a recent study[5] shows that this is what we can expect with global warming. In this study, Bressler concluded that "When the reduced sensitivity to heat associated with rising incomes, such as greater ability to invest in air conditioning, is accounted for, the expected end-of-century increase in the global mortality rate is 1.1% [95% CI 0.4-1.9%] in RCP 4.5 and 4.2% [95% CI 1.8-6.7%] in RCP 8.5."[5]

These kinds of projections are based on model simulations, and they can't possibly account for all factors affecting temperature-related mortality with warming, hence the large CIs in Bressler's estimates for increases in mortality rates. However, what should be clear is that the "cold kills more than heat, so global warming saves lives" logic is flawed on multiple levels. It's based on a superficial understanding of current conditions and logically fallacious reasoning about how mortality rates will change with warming. As best as we can tell right now, even using an MMT metric, global warming will lead to an increase in temperature-related mortality, even if some areas (like the United States) may see a slight benefit in the short-term from global warming.

Conclusion

And this is only considering temperature-related deaths - that is, deaths that directly related to temperature. It does not account for many of the other factors that may cause an increase in mortality with warming, such as water scarcity in areas dependent on glacier-fed water sources after the glaciers disappear. Lee and Dessler write,

The health impacts of extreme heat are just one of many health impacts of climate change. As such, this research should not be interpreted as suggesting that climate change will yield net health benefits for low levels of warming.

And Gasparrini also wrote in a

fact check concerning Bjorn Lomborg's misuse of his paper,

[Our] study contributes evidence only to ‘direct’ effects of temperature on human health. As a matter of fact, this is likely to represent a minor part of the total excess mortality and morbidity due to a changing climate.

In order for prepare for living in a warming world, we need to get an accurate assessment of the risks associated with climate change, including all the health impacts from a warming world; these should be taken into consideration. The above studies focus on one aspect of this overall picture - how temperature-related death are affected by warming. But with a full picture of the health risks associated with a warming world, we can get a better sense of the importance of not just adapting to climate changes but also assigning the correct priorities for mitigation to save both lives and money.

Note: I updated graphs on 1/23/2026.

References:

[1] Zhao, Q., Guo, Y., Ye, T., Gasparrini, A., Tong, S., Overcenco, A., … Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. (2021). Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(7), e415–e425. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00081-4.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00081-4[2] Gasparrini, A., Guo, Y., Hashizume, M., Lavigne, E., Zanobetti, A., Schwartz, J., … Armstrong, B. (2015). Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. The Lancet, 386(9991), 369–375. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62114-0

[3] Gasparrini, A., Guo, Y., Sera, F., Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M., Huber, V., Tong, S., et al. (2017). Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios. The Lancet Planetary Health, 1(9), e360–e367.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(17)30156-0 [4] Lee, J., & Dessler, A. E. (2023). Future temperature-related deaths in the U.S.: The impact of climate change, demographics, and adaptation. GeoHealth, 7, e2023GH000799.

https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GH000799[5] Bressler RD, Moore FC, Rennert K, Anthoff D. Estimates of country level temperature-related mortality damage functions. Sci Rep. 2021 Oct 13;11(1):20282. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99156-5. PMID: 34645834; PMCID: PMC8514527.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment